The Christmas Mountains add a West Texas twist to TXST scientific study

By Matt Joyce

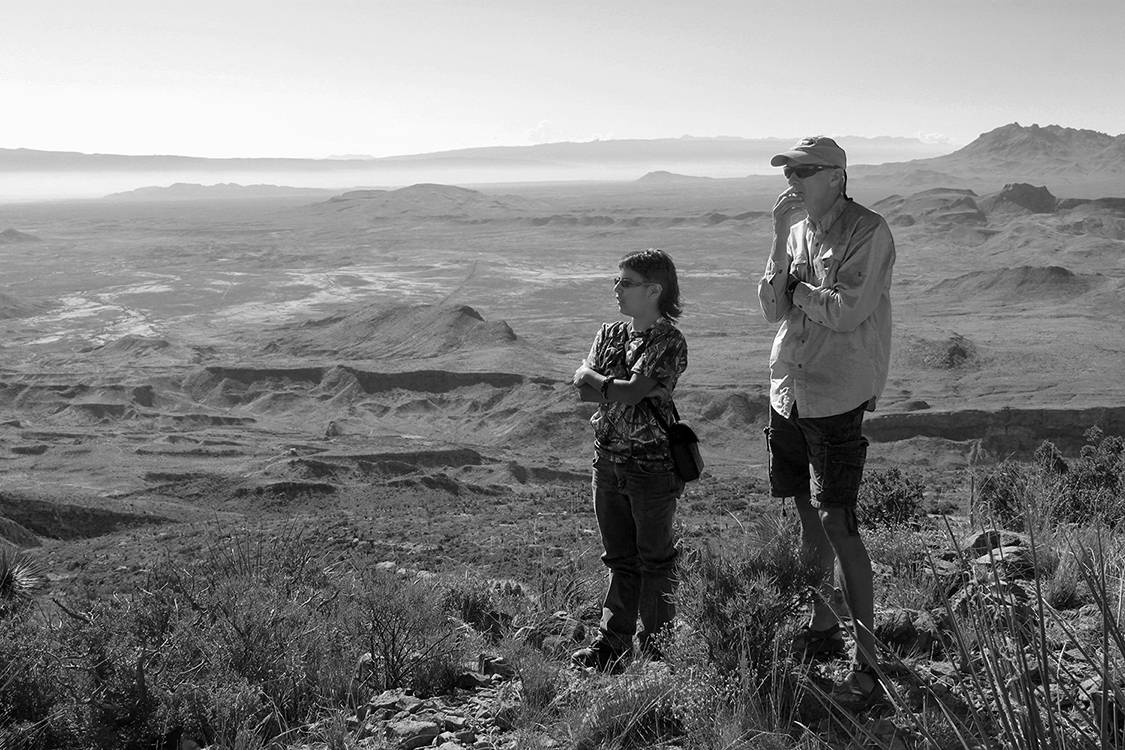

Sunshine bakes the Chihuahuan Desert floor on a clear May morning as hikers pick their way through rocky hills and washes. Decked out in hats and boots, the hikers hunch over mounds of shale and scan the ground for fossilized Tyrannosaurus rex bones and petrified cypress wood.

Here in a geological formation called the Cretaceous Aguja, near Big Bend National Park, “the upper shale is one of the most prolific areas when it comes to dinosaur fossils,” explains Dr. Thomas Shiller, a geology professor at Sul Ross State University in Alpine.

But this fossil-hunting party isn’t a formal paleontology expedition. Rather, it’s a motley mix of desert-lovers — an astrophysicist, a medical school professor, and a logistics professional among them — exploring on a field trip that’s part of the Christmas Mountains Research Symposium.

Texas State University biology professor Dr. David Lemke produces the annual symposium, which is held each May at Terlingua Ranch Lodge, at the foot of the Christmas Mountains. The symposium convenes scientists from various disciplines, nonprofits, governmental agencies, landowners, and members of the public to network and share research centered around the Big Bend region.

“A cross-disciplinary research symposium is a rare phenomenon,” says Tim Gibbs, an archeologist at Big Bend Ranch State Park. “I find it remarkable — learning the interesting perspectives that someone like an entomologist might bring to a question that an archeologist would never think of.”

The Texas State University System, of which TXST is a member, owns the 9,270-acre Christmas Mountains property. It has promoted research enterprise at the range since the state deeded the property to the system in 2011 with the goal of making it the “largest outdoor classroom in Texas.”

A cosponsor of the symposium, TSUS also permits public access for motorists, hikers, and horseback riders. TSUS is also planning to build a field research station at the base of the mountains. Using $11 million in funding appropriated by the Texas Legislature in 2021, the system’s plans call for the construction of lodging, lab space, and classrooms for visiting researchers and students.

The tract presents researchers with an opportunity to study subjects ranging from erosion to whiptail lizards to the night sky. The property contains about six peaks, topping out at Christmas Mountain’s 5,728-foot summit. A 3.5-mile unpaved road winds to the peak through habitats of desert scrub and grasslands, montane scrub, and arroyos. From the summit, views of Big Bend National Park reveal the famed Chisos Mountains and Santa Elena Canyon in the distance.

The rugged Christmas Mountains were shaped over millennia by ancient seas, volcanic eruptions, vertical faulting, and erosion. The tract contains evidence of human habitation throughout time — from Indigenous tribes to cattle ranchers who arrived in the 1880s, and goat ranchers and miners of the early 1900s.

But the region’s isolation and punishing desert climate are hard on agricultural and industrial businesses. As government agencies acquired land to create Big Bend National Park in the 20th century, the Christmas Mountains eventually became a hunting ranch, where sportsmen chased deer, mountain lions, and black bears.

In the early 1990s, environmental groups acquired the property with the intent of donating it to Big Bend National Park. Complications arose, leading the land to be donated to the state of Texas subject to a conservation easement that prohibited future development while allowing hunting for wildlife management. About 15 years later, the General Land Office pursued selling the land but ultimately deeded it to TSUS.

“Because of the limited access in the past, we don’t really know much about the Christmas Mountains,” Lemke says. “Now that the university system owns it, it’s a preserve, and it won’t be disturbed. It will always be there for educational and research purposes. That’s why it’s important to do baseline studies to document what’s there now.”

Lemke, who started the Christmas Mountains Symposium in 2013, is one of several TXST scientists to conduct research on the property. For over 10 years, he’s been working on a vegetation survey of the mountain range, recording more than 1,000 plants from the area.

“I’ve been trying to identify everything that’s out there,” he says. “It’s got everything from low-elevation desert plant communities to mountain scrub communities. With the different canyons and arroyos, it’s surprisingly diverse, more so than you might think when you first look.”

TSUS’ ownership of the Christmas Mountains and TXST’s symposium have generated interest among nearby private landowners. The range neighbors the 200,000-acre Terlingua Ranch, a loose affiliation of some 5,000 property owners governed by the Property Owners Association of Terlingua Ranch.

Resident Larry Sunderland serves on the board of the Property Owners Association and chairs its Water Committee. At the May symposium, he says, he learned about possible strategies for managing water on his land and had the opportunity to connect with a regional hydrologist.

“I’m trying to do things that will slow water down on my land, put it into the water table, and help bring back Corazon Creek,” Sunderland says. “This region and this ranch are at an inflection point. We will milk this land for all it is worth and move on, or we will have to figure out how to live within it, on its terms. The most important thing that Texas State has brought is connection to the schools, the agencies, nonprofits, and NGOs whose purpose is to protect, preserve, and restore wild places.”

Neighboring property owners are the hosts of the morning paleontology field trip, which takes place just east of the Christmas Mountains. Shiller, an expert in Big Bend paleontology, helps participants identify their possible finds, including at least one T. rex tooth.

He says the symposium offers a unique opportunity to collaborate with people outside of his discipline, as well as a chance for graduate and undergraduate students to practice presenting their research in a relatively casual setting.

Lauren Chappell, who graduated from TXST in May with a master’s degree in Aquatic Resources-Aquatic Biology, attended the May symposium to present her thesis research on the resilience of Nueces River fish populations during extreme drought.

“It’s really cool to be able to get a bunch of people in the same room to talk about this ecosystem that we all love,” Chappell says. “It’s amazing how many landowners are here. There should be a symposium like this for each ecoregion of Texas.” ★