TXST alum Ben Pfeiffer is a leading advocate for lightning bugs

By Robyn Ross

On a warm May evening, Ben Pfeiffer was sitting in the bed of his pickup truck on a roadside near the Guadalupe River in Comal County, counting fireflies. It had been a fantastic year for lightning bugs, and Pfeiffer, the state’s leading avocational firefly researcher, had counted four or five different species in a single night.

Pfeiffer — a 2005 Texas State University biology graduate — watched as one species of fireflies synchronized its flashes, blinking yellow-green in the trees in unison. Suddenly, a bright amber light streaked across the nearby field, so bright it illuminated the grass below.

“It looked like a supernova went off in this field,” Pfeiffer remembers. “It was the brightest flash I had ever seen. The other fireflies just stopped and started to flash even more.”

Pfeiffer leapt off his truck with his net and raced toward the trailing amber light. Based on the color and flash pattern, as well as the fact that the firefly had been solo rather than in a group, he knew it was a Pyractomena vexillaria. The species hadn’t been documented in Comal County since the 1940s.

Pfeiffer didn’t catch the firefly that night, but he logged the sighting in his notes. Later, he was able to use it to inform an extinction risk assessment for the International Union for Conservation of Nature, a global nonprofit. The group now lists the species as endangered. Pfeiffer also gave the species its common name: the Amber Comet.

Since 2009, Pfeiffer — a self-employed digital entrepreneur who lives in New Braunfels — has dedicated most of his free time to studying fireflies and teaching other people about them. As founder of the nonprofit Firefly Conservation & Research, he has carved out a space in the national firefly community as the go-to expert in the state of Texas. He and other firefly advocates are working to protect fireflies as the insects’ populations decline due to light pollution and habitat loss.

“Ben is by far the most dedicated firefly person in the state of Texas,” says Candace Fallon, a senior conservation biologist at Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation and a member of the IUCN firefly specialist group. Fallon says Pfeiffer is one of fewer than a dozen firefly experts in the country, most of whom are concentrated on the East Coast. “That’s why people like Ben are so incredibly valuable.”

A native Texan, Pfeiffer grew up spending time outdoors on family land near Fredericksburg and Jourdanton. He says when he was a teenager, he took a family cruise to Puerto Rico that included a kayak excursion into a bioluminescent bay. At dusk, he paddled through a mangrove forest into a lagoon where tiny organisms called dinoflagellates lit the water with a bluish-white glow. The experience sparked Pfeiffer’s fascination with bioluminescence.

Pfeiffer majored in biology at Texas State, focusing on genetics, plant physiology, and evolutionary studies. He says his evolution class with Associate Professor James Ott (now retired) stands out as one that required “grit and determination” and set a standard for scientific rigor. He also learned about the process of scientific research by assisting a graduate student who was studying the endangered fountain darter that lives in the San Marcos River.

For his day job, Pfeiffer runs a search engine optimization and digital marketing agency he started while a student at Texas State. He formerly bought and sold domain names, and in late 2008, still fascinated with bioluminescence, he bought the domain name “firefly.org.” Soon after, he heard a news report about the decline of firefly populations around the country. He decided to research fireflies in Texas and use the website to share his findings.

For the next five years, Pfeiffer became a self-taught entomologist by apprenticing himself to senior researchers across the state. He figured out how to conduct field work, pin insects, and organize specimens. He learned how to determine the genus and species of a firefly specimen and how to recognize distinct flash patterns.

“People think fireflies come out all at once,” he says. “But really, throughout the course of the night, in a two-hour period, multiple species come out at different times. You have a progression of how the light show happens throughout the evening.”

Texas has about 40 different species in the firefly family known as Lampyridae, including both diurnal and nighttime flying species, Pfeiffer says. Becoming expert in all of them is challenging because of the state’s many ecoregions, each with its own firefly populations.

When Pfeiffer does field work, he stays at an observation site from just before dusk until 10 p.m. He watches which species emerge, takes notes, records video if possible, and collects specimens. He has found vast species diversity near the Devils River; in Sabine County in East Texas; in pockets of the Hill Country; and near the border in the Rio Grande Valley.

“Ben has done a great job of taking on Texas, which is really needed,” says Tennessee-based independent researcher Lynn Faust, author of a field guide to fireflies of eastern and central North America. “Texas could be its own world in fireflies. There are a lot of unusual species and very little known about them. Ben is doing a good thing, and hopefully he will mentor the next generation.”

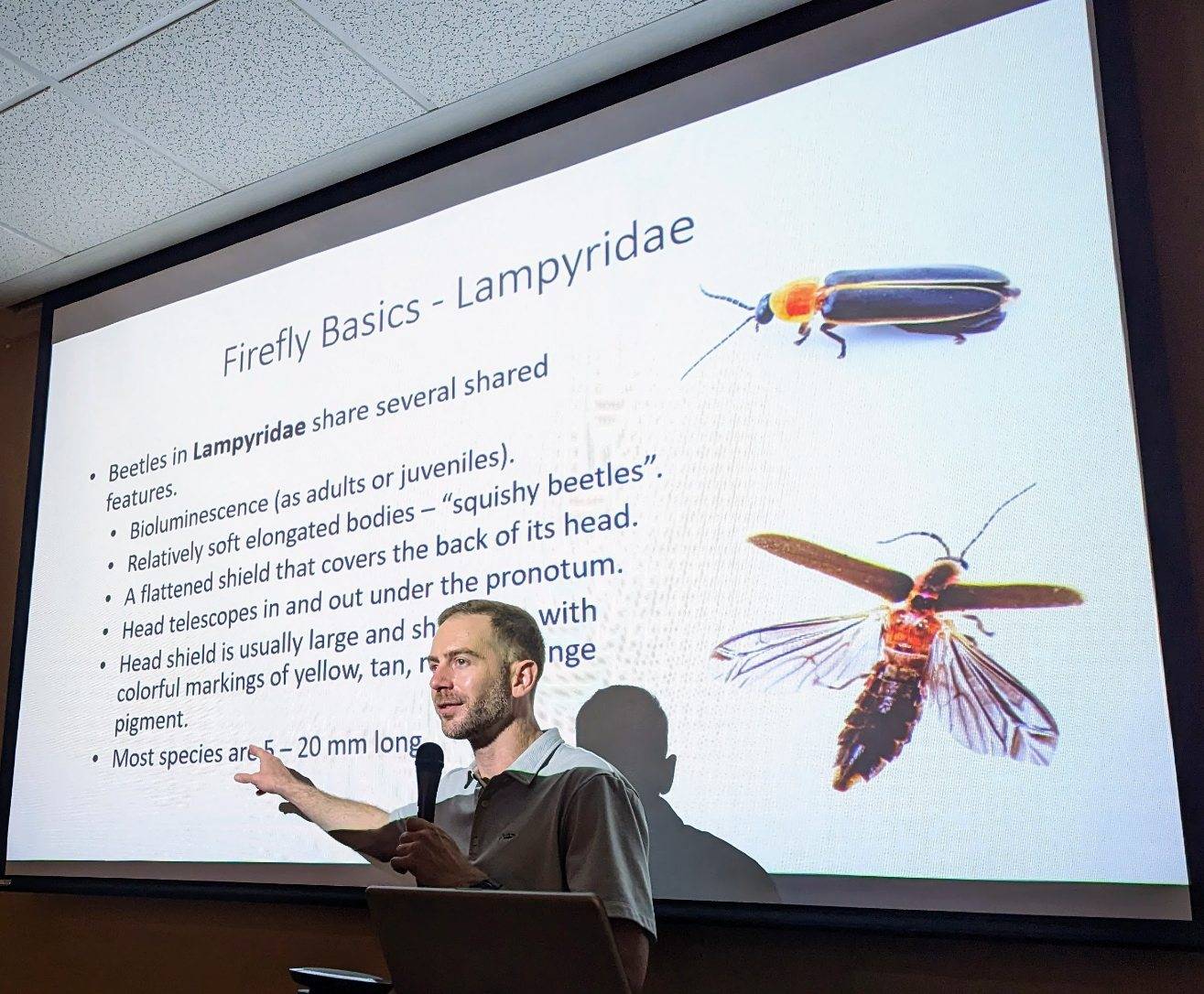

Raising awareness of fireflies has been a consistent part of Pfeiffer’s work. He travels the state speaking to master naturalists, conservation groups, nature centers, and libraries. At these talks, he introduces the most common Texas fireflies and explains how people can protect them. Through Firefly Conservation & Research, he designates “certified firefly habitat” recognition to residential and rural landowners, nature preserves, and state parks that meet firefly-friendly criteria, raising awareness of the insects’ needs.

Pfeiffer’s Dark Skies and Fireflies event typically takes place on the third Saturday of May at the Crescent Bend Nature Park in Schertz. Last May, the event drew a troop of 40 Girl Scouts who listened raptly to his presentation and then set out to find fireflies in the summer night.

“I see their eyes light up when they see one, sometimes for the first time,” Pfeiffer says. “It’s so rewarding that I was able to help inspire them and their love for nature in that way.” ★

Ben Pfeiffer presents firefly information to participants at a Dark Skies and Fireflies event in Schertz. Photo courtesy Ben Pfeiffer

Enhancing Firefly Habitat

Development is threatening firefly populations across Texas. Here are five ways you can protect the insects in your area. Learn more at Firefly Conservation & Research’s habitat page.

- Reduce light pollution. Fireflies flash to find a mate, and when habitats are lit at night, fireflies can’t find one another. Turn off unnecessary indoor and outdoor lights after dark. Shield outdoor fixtures so the light is directed downward or try using motion-detecting lights instead. Look for bulbs with an amber, rather than bright white or bluish, glow. Ask your HOA and city to turn off unnecessary lights and replace white bulbs with amber-hued ones.

- Make your yard firefly friendly. Limit your use of pesticides and lawn chemicals. Consult with a local organic nursery or a nearby chapter of Texas Master Naturalists for alternatives.

- Conserve riparian corridors. If you live along a creek or river, leave the bank where the water meets the land undisturbed. When people mow all the way to the edges of streams and replace native plants with manicured lawns, they’re eliminating fireflies’ favorite habitat.

- Resist the urge to rake up all the leaves in your yard. Fireflies lay eggs in leaf litter. “A lot of times, when people rake up their leaf litter, they are actually raking up firefly larvae that are underneath,” Pfeiffer says.

- Advocate for fireflies. Outside your own backyard, support policies that protect firefly habitat such as parks bonds and measures that conserve land from development.