Kristi Duplichen harnesses a collaborative work ethic forged at TXST to manage International Space Station logistics

By Anthony Head

For people fascinated with the sky, the upper floors of the Albert B. Alkek Library are an interesting place to be.

“My son’s girlfriend is at Texas State and sent me a photo from the library, showing the clouds,” says Kristi Duplichen, a 1999 physics graduate of Texas State University. “I told her she had to be there when a norther comes through. When I was there, I loved to watch the clouds roll in.”

Duplichen’s love of the sky dovetails naturally with her career at NASA, where she works as deputy manager of the International Space Station Transportation Integration Office. Earlier this year, NASA recognized Duplichen and other women for their contributions to the International Space Station program and the inspiration they provide for women at NASA and girls aspiring to the science, technology, engineering, and math fields.

“I have had great role models and mentors during my career,” Duplichen says. “I am proud to be among women who have made and are making such an impact on our human spaceflight program with their dedication and leadership.”

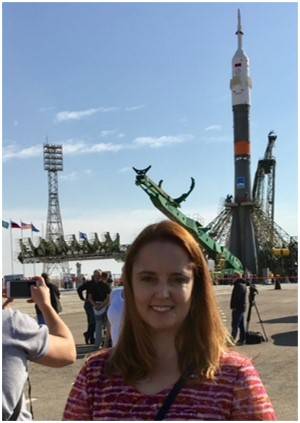

Though Duplichen is based at Johnson Space Center in Houston, she travels to Kennedy Space Center in Florida to watch rockets lift off as they depart on missions to the International Space Station. “They are very powerful,” Duplichen says. “Very loud. You feel it.”

Duplichen has experienced rocket and space shuttle launches from several unique perspectives for over two decades. These days she collaborates with companies like Northrop Grumman and SpaceX to deliver crew, cargo, and science experiments to the space station, focusing on the logistics of sending people and things up to space and getting them back down to Earth.

“A lot of people don’t realize the space station is only about 250 miles above the Earth,” Duplichen says. “It’s not millions of miles away. We’re trying to boost low-Earth-orbit commercialization. There are several companies trying to use it more. It’s a great need, and we’re getting a lot of results from the science.”

Duplichen’s interest in space operations stretches back to her childhood in East Bernard, about 50 miles southwest of Houston. The town was small, without much light pollution, allowing Duplichen opportunities for a fair amount of stargazing and the kind of wondering that comes with it.

She also worked in the family auto parts business, and with that background she enrolled at Texas State in 1995 as a marketing major. Perhaps it was the great views from Alkek Library, but Duplichen couldn’t shake the lure of the skies and contemplated switching majors. “I told myself that I’d take a physics class, and if I made an A, I’d switch.”

It was a significant personal wager, she admits, and one that changed her life — “I made an A.”

Despite loving math and science, Duplichen still recognized that, “Physics wasn’t something that came naturally. It took a lot of determination to finish.”

Dr. Heather Galloway, dean of the Honors College and professor of physics at Texas State, was an assistant professor at that time. “I was the only female physics faculty member, and Kristi was one of the few female physics students,” Galloway recalls. “She was a super hardworking student — eager to do better and looking for ways to improve.”

For most of college, Duplichen and Amy Rule were roommates. Rule noticed Duplichen’s approach to tackling physics included a distinct strategy: study groups. “She always had a group,” says Rule, now an elementary school counselor in Bulverde. “She was very committed to her study groups. She was prepared for whoever she was going to study with.” (Rule adds that she was part of an important group that assembled on Thursday nights to eat pizza and watch Friends. “That was a big thing we did with a group.”)

Physics degree in hand, Duplichen attended a Texas State University-hosted job fair, where she found a job in Houston with the spaceflight operations company United Space Alliance. “I’ve wanted to work at NASA my entire life, and they had opportunities to do that,” she says.

Duplichen became a flight controller at one of the most significant times in NASA history. The age of the International Space Station was dawning, and Duplichen worked inside the mission control building when the station was being assembled in space — low-Earth-orbit, to be specific — with materials and crews from the U.S., Canada, Russia, Europe, and Japan.

Once built and crewed, the station regularly required new crews and equipment and new science experiments. “We’d take goods back and forth to the crew members on board the space station, anything from replacement hardware to clean T-shirts to food to tools,” Duplichen says. “You have to have a system. You have to do it efficiently, including bringing everything back.”

Duplichen had originally intended to pursue a master’s degree in engineering but chose a master of business administration (which she earned in 2004 from the University of Houston-Clear Lake). “By then I’d been working with astronauts for a couple years, and I understood that it really takes a village to make this work,” she says. “We need accountants, finance experts, attorneys, medical teams, and marketing. There’s a whole support system, and I enjoy being part of that.”

In 2006, Duplichen began working directly for NASA. Her jobs have involved keeping astronauts safe while on-orbit; managing contracts that ensure space hardware destined to and from the space station is properly packed and loaded; and managing contracts providing Russian logistics and language support.

Tricia Mack, customer integration manager for the Transportation Integration Office, has worked for NASA for 31 years, including on various teams with Duplichen. She describes her colleague as a strategic thinker. “She cares about our team,” Mack says. “She’s fantastic about working together in our office and across the entire program.”

Duplichen lives in Pearland with her husband, David Duplichen — a TXST grad working in healthcare information technology — and their two children. “I don’t do hard physics equations anymore," she admits," but I kept them to prove to my children that I’ve done them.”

Her science and academic background remain valuable in her career. “Being able to talk through problems with others comes from having really great study groups when I was in school, talking through problems that none of us knew how to solve at first,” Duplichen says. “That dynamic was really helpful.”

The views from Alkek Library didn’t hurt either. ★