In 1927, 19-year-old Lyndon Baines Johnson borrowed $75 and hitchhiked from Johnson City, in the heart of the Texas Hill Country, to San Marcos to enroll at Southwest Texas State Teachers College. But it was not as soon as his mother would have liked . . .

Planting the Seeds

At TXST, LBJ grew from an ambivalent youth into an ascendent statesman

For years, Rebekah Johnson tried to instill in her son a love of education, to no avail. As LBJ admitted later, he likely wouldn’t have made it through high school without her browbeating him into minding his studies. Even then, he rejected her pleas for him to attend college. Instead, the young man went west to California with a group of friends in a broken-down Model T, devoid of a roof and windshield, in search of adventure and riches that never came. Johnson worked a series of menial jobs before retreating home after less than a year, “thinner and more homesick.” Maybe a little chastened, too. He moved back into his parents’ house and took a job his father got him on a road crew. Faced with the prospect of a hard life of monotonous blue-collar work—and after his arrest in a brawl at a Saturday night dance—Johnson gave in to his mother’s wishes. He set his sights on a new beginning in San Marcos and the possibility of a future as an educator.

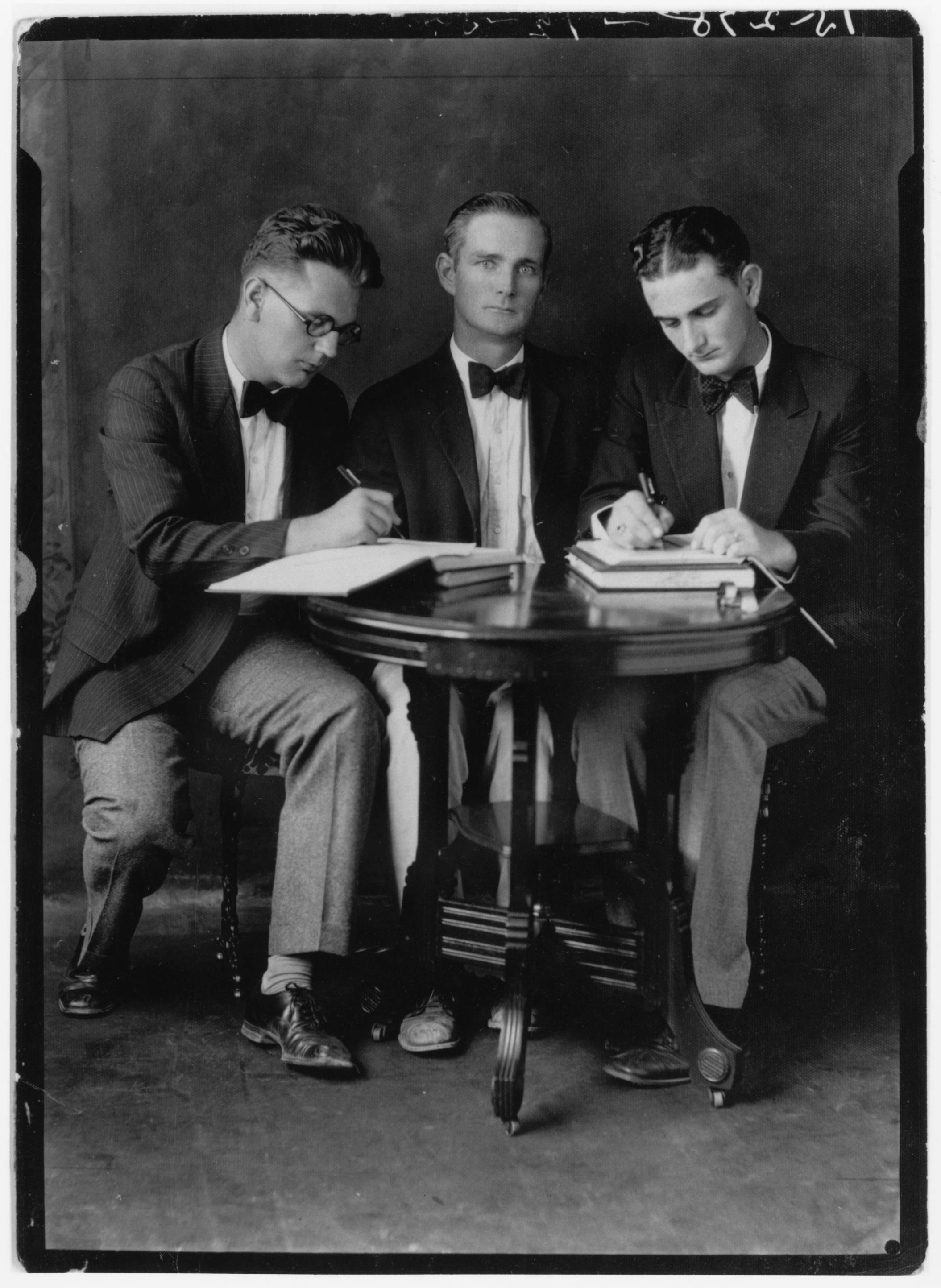

As Johnson settled into campus life, he saw new horizons—and others saw his potential. While he would never be more than a B student, he distinguished himself in other significant and formative ways that portended a promising future. In his first year, Johnson was the only freshman to make the school’s debate team, proving so gifted that the coach gave him the final word at the state championship, where the team won a decisive victory over Sam Houston State Teachers College.

Johnson might have been able to achieve more academically but, according to a school dean, “had too many irons in the fire.” Many of the “irons” related to his tenuous financial situation. Johnson struggled throughout his college years to pay for tuition and living expenses. “Sometimes I wondered what the next day could bring that could exceed the hardship of the day before,” he recalled.

To make ends meet, he worked at least a dozen odd jobs, including as a janitor and door-to-door sock salesman. He proved especially successful at the latter, displaying an early form of what would later become known in political circles as “The Johnson Treatment”—his preternatural ability to bend people to his will. “I bought socks from him,” recalled one of Johnson’s former professors. “Everybody did. You couldn’t resist.”

College President Dr. C. E. Evans was so taken with Johnson’s drive that he offered him the tiny room over his garage as living quarters to help with expenses. Johnson lived there for three years, showering in the school’s gymnasium. At Johnson’s urging, Evans also hired him as an assistant to his executive assistant, an opportunity that provided Johnson with a prime vantage point on the college’s seat of power and Evans’ strong leadership.

Not surprisingly, Johnson found his own footing on campus as a leader. He was the co-founder of Alpha & Omega, a secret college political organization, and the editor of The College Star, the weekly campus newspaper, an elected position that he held for two years. Those experiences, plus his studies, gave him an early understanding of parliamentary procedure and the way government worked. His government professor and debate coach, Howard Greene, was impressed not only with Johnson’s debating skills but also with his raw political ability, recognizing that politics would be a logical career path. “He was clearly the best student in government and politics I had ever had the pleasure of teaching,” Greene said.

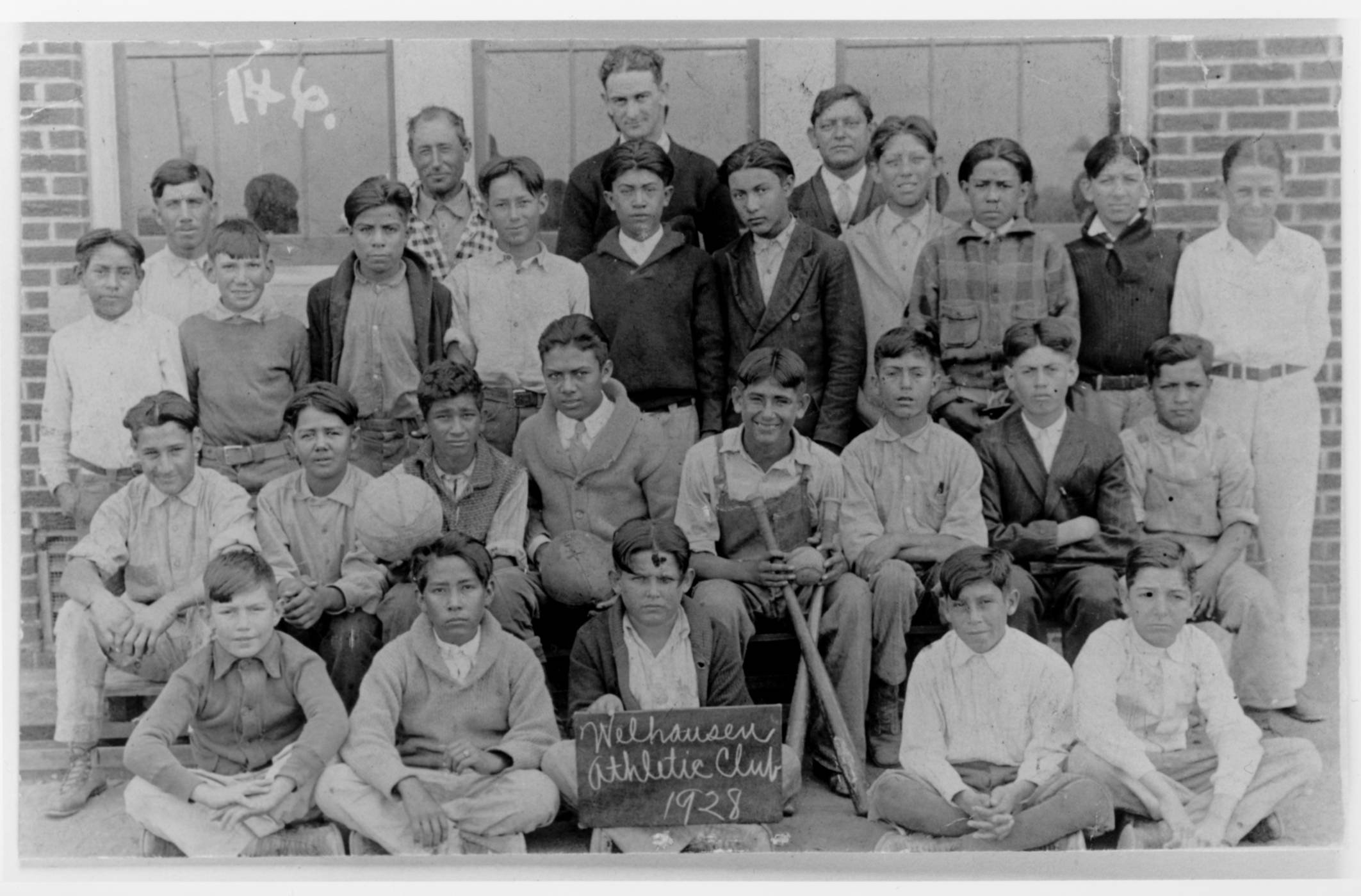

Evans saw LBJ’s potential in the political arena, too. Sensing that LBJ was a “competitive animal,” he dissuaded him from becoming a teacher, suggesting that that there wouldn’t be enough competition in the classroom to suit him. Johnson had been keenly interested in teaching—cash-strapped, he even left San Marcos between his junior and senior years to teach at a segregated Mexican American school in Cotulla. The experience showed him firsthand the pain of poverty and prejudice and left a searing impact on his consciousness. “My ambition, [Evans] said, was laudable,” Johnson recalled. “But he thought that being a public servant would be best because I’d have to meet the challenges of the time at the very moment they were happening.”

As with his mother’s admonition to go to college, LBJ heeded Evans’ advice, albeit belatedly. After graduating from Southwest Texas State in 1930, he became a teacher in Houston before embarking a year later on a career in Washington—first as a congressional aide, then as an elected official, ascending his way up the political ladder to become a congressman, senator, vice president, and, of course, president.

Johnson’s transformational Great Society legislation included the Civil Rights Act, Voting Rights Act, Fair Housing Act, Immigration Act, Clean Air Act, Medicare, and Medicaid. But the once recalcitrant, unruly young man who had initially shunned college wished to be known as “the education president.” Among the programs he championed were the creation of Head Start and a profusion of federal aid to education for the first time through the Elementary and Secondary Education Act and the Higher Education Act, dramatically improving the national education landscape.

In 1965, Johnson returned to TXST to sign the Higher Education Act into law, underscoring the importance of his own college experience and capping one of the nation’s most influential educational journeys. Fittingly, LBJ returned to his alma mater in 1965 to usher the Higher Education Act into law. After applying his jagged signature to the bill, he harkened back to his days on campus over three decades earlier.

Here the seeds were planted from which grew my firm conviction that for the individual, education is the path to achievement and fulfillment; for the nation it is a path to a society that is not only free but civilized; and for the world, it is the path to peace — for it is education that places reason over force.