In ‘¡Viva Terlingua! The Big Bang of Texas Music,’ The Wittliff Collections at TXST explores the origins of outlaw country

By Hector Saldaña

It was a moment as unlikely as it was epic. Fifty years ago, New York-born singer-songwriter Jerry Jeff Walker found his voice in a remote Hill Country dance hall.

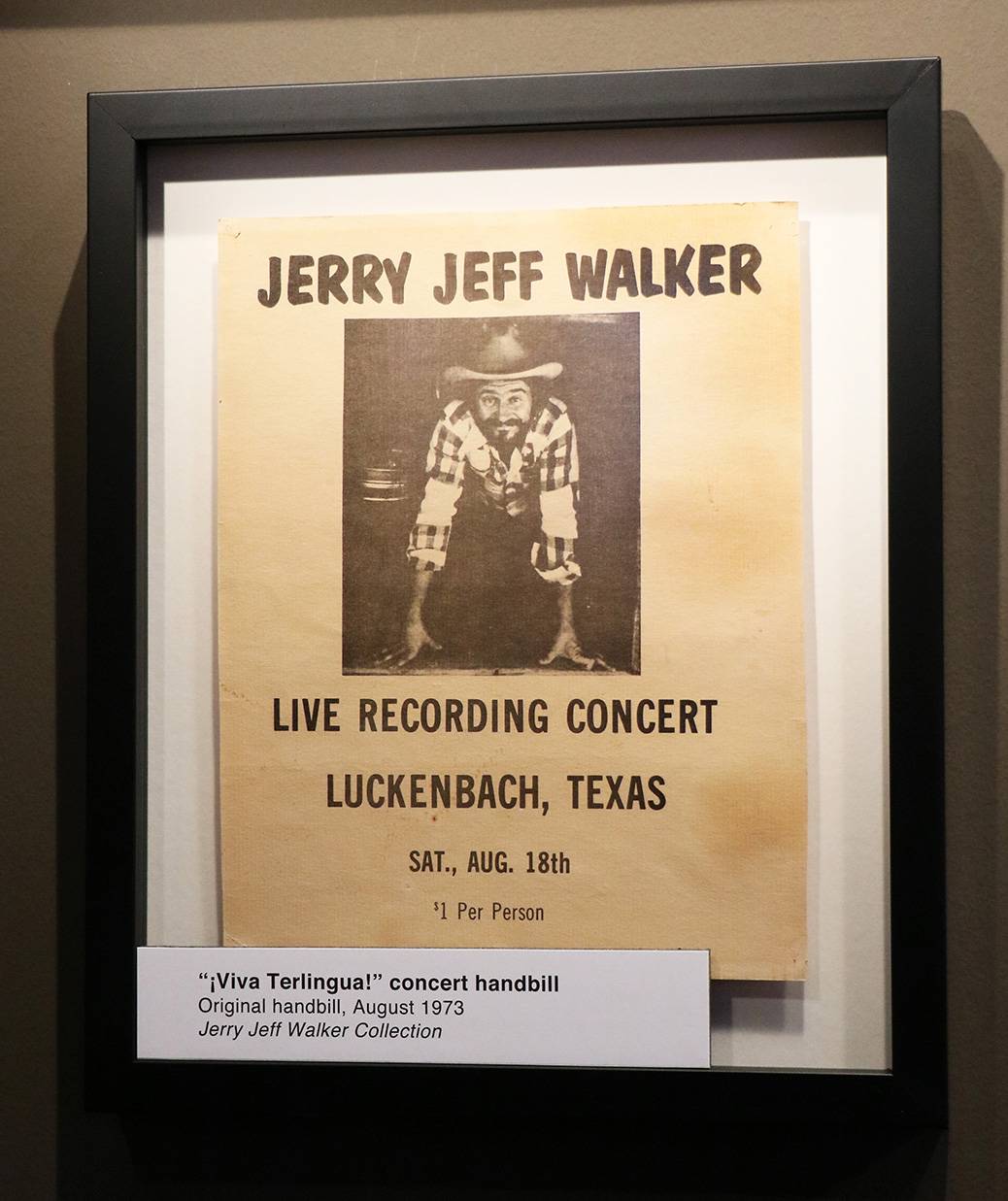

In sweltering August temperatures, Walker and the Lost Gonzo Band gathered for a week of rehearsals and a raucous performance in the speck of a settlement called Luckenbach to create what today occupies hallowed status in Texas music and the world of outlaw country. The resulting album—1973’s ¡Viva Terlingua!—remains a quintessential Texas record for its songs, musicians, locale, culture, aesthetic, and the songwriters represented.

This summer, The Wittliff Collections at Texas State University opened “¡Viva Terlingua! The Big Bang of Texas Music,” a major new exhibit that celebrates the making of Walker’s most iconic album, one that embodied an era and staked a distinctive musical brand. It runs through Spring 2025.

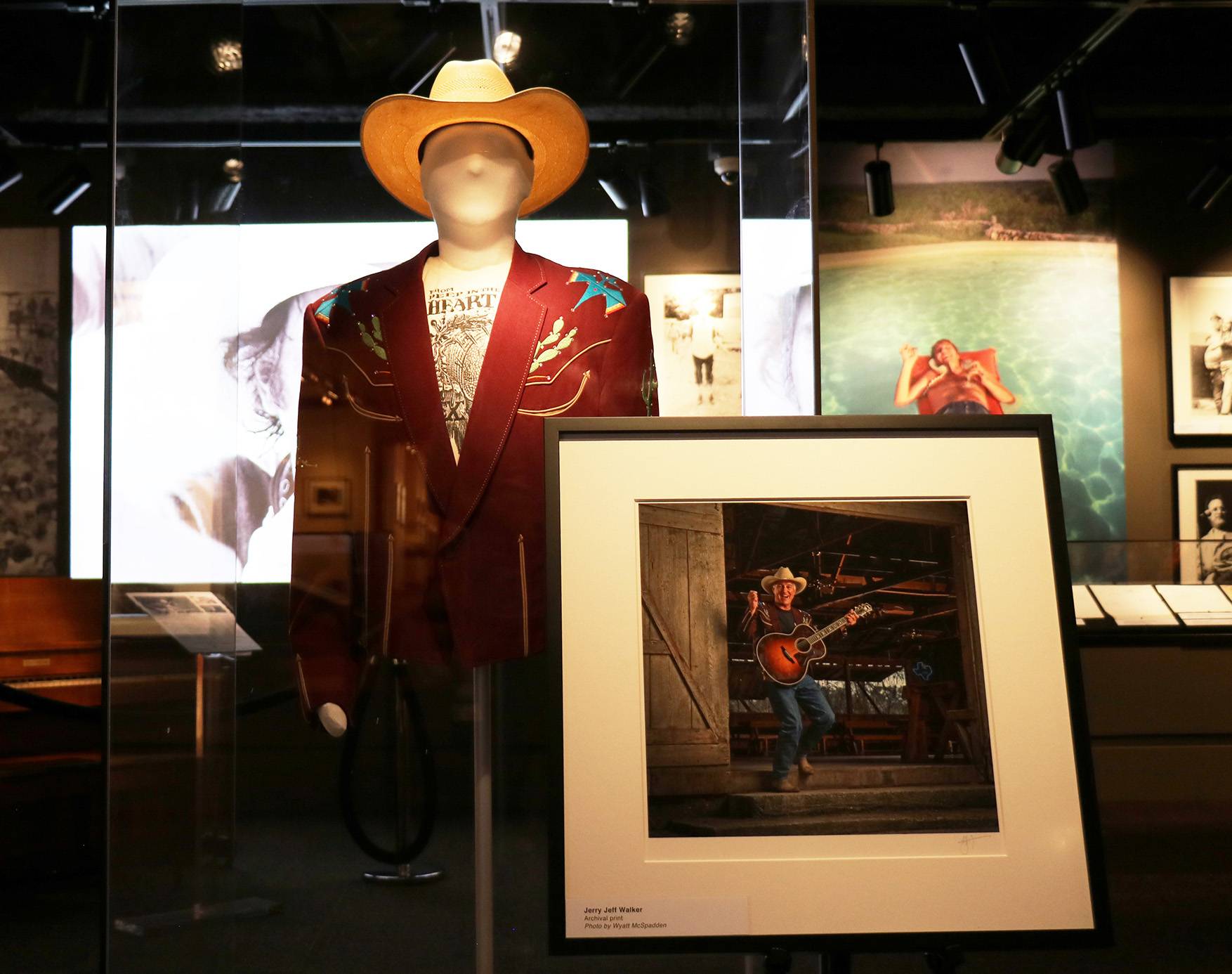

Photos, instruments, and attire bring the historic recording sessions to life in The Wittliff exhibit. Photos by Mark Willenborg

The new exhibit stems from the discovery of about an hour of unreleased material from the ¡Viva Terlingua! sessions. While researching and digitizing Walker’s master tapes, Wittliff curators and archivists found the additional audio from mid-August 1973.

The 16-track analog master tapes are the heart and soul of the exhibit, which offers the public its first opportunity to hear the restored audio. Nashville author and country music insider Holly Gleason called the discovery “a major wow.”

Entering the exhibit, visitors will hear that fresh audio playing on a loop: rehearsals, unreleased live performances, alternative takes, unfinished music, remixes, and plain joking around.

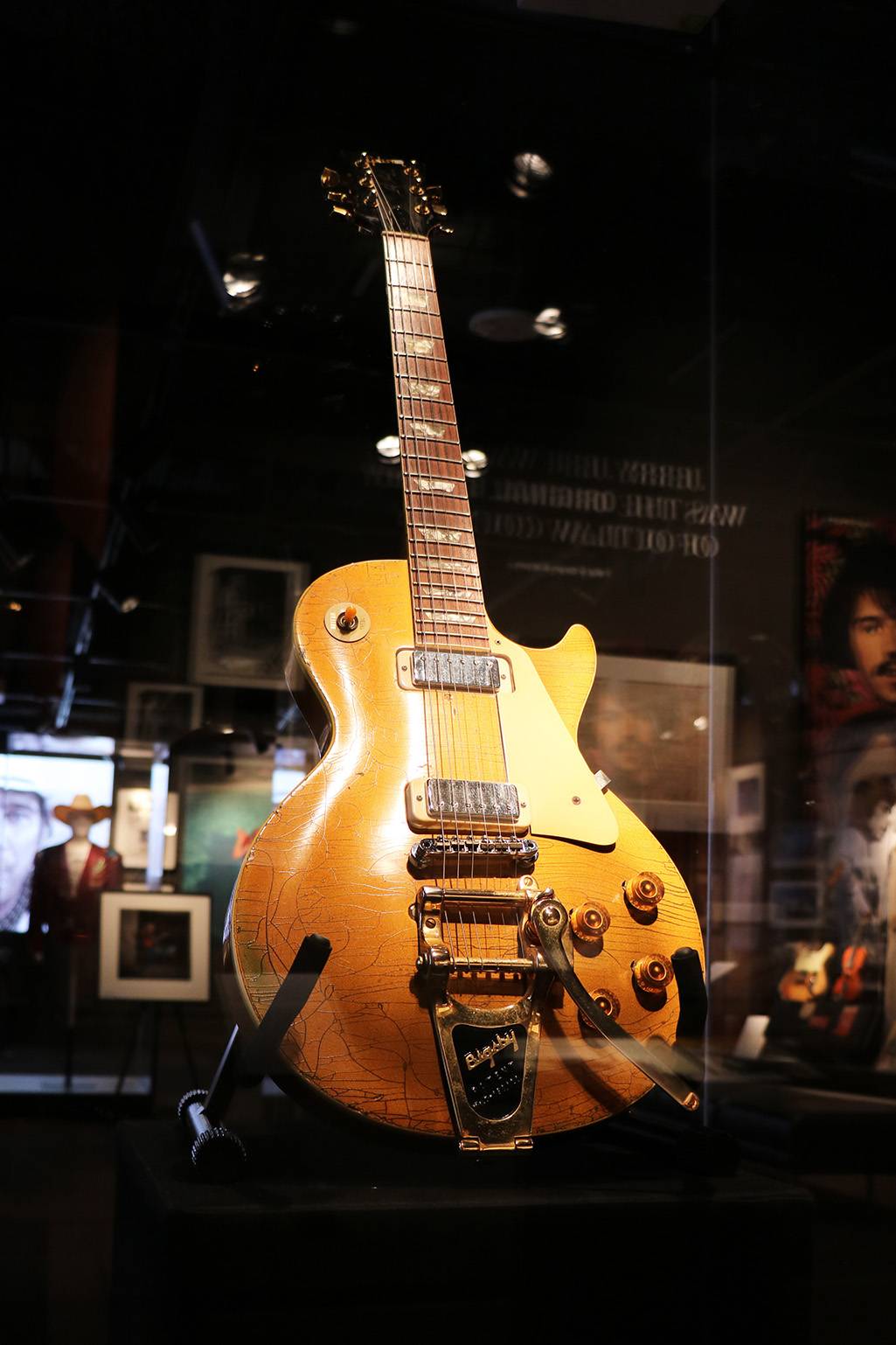

The audio loop provides a soundtrack to rarely seen artifacts, including instruments used in the making of the album, handwritten lyrics, and clothing. At the center of the gallery, a favorite hat of Walker’s and one of his Gibson guitars—on loan from singer-songwriter Robert Earl Keen—add a personal link to the Luckenbach days.

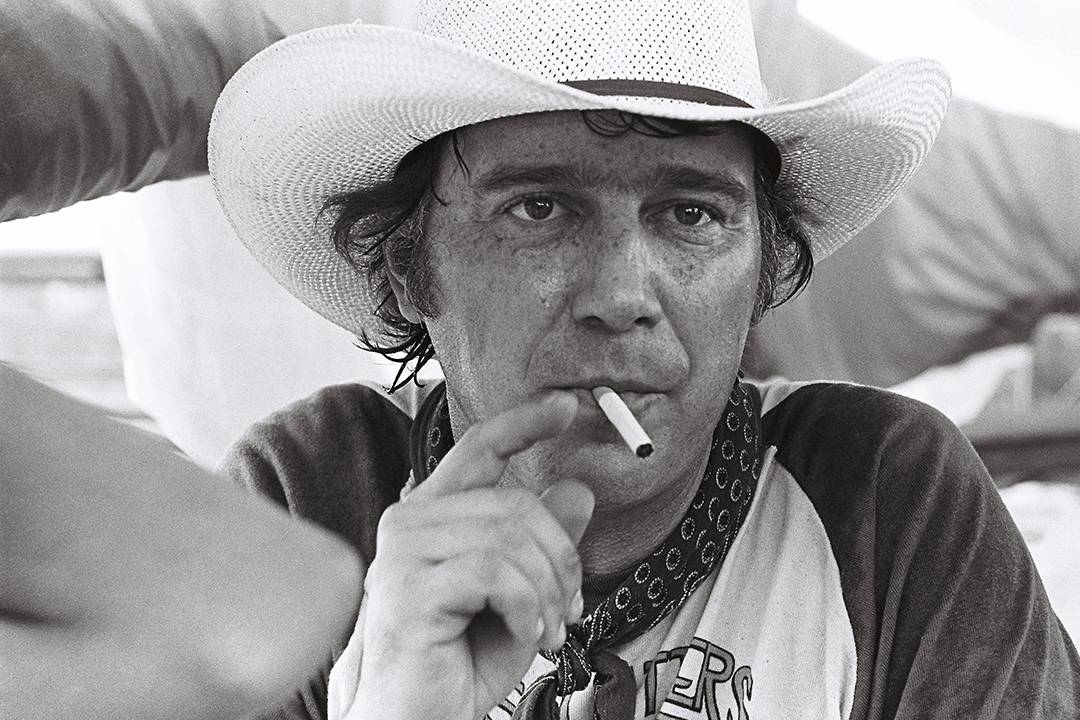

Historic photographs by Scott Newton, Melinda Wickman Swearingen, Burton Wilson, Jim McGuire, Gary P. Nunn, and Wyatt McSpadden bring the exhibit to life and capture the fresh-faced exuberance of the times.

Jerry Jeff Walker performed Guy Clark’s “L.A Freeway” at the Luckenbach show. The live recording is among the newly discovered, never-released audio that is part of the exhibit.

Walker passed away on Oct. 23, 2020, at the age 78. A few years before his death, he and his wife donated his archives to The Wittliff Collections. The collection consists of dozens of boxes of handwritten lyrics, poems, notes, correspondence, photographs, posters, manuscripts, project ideas, newsletters, stage clothing, ephemera—and more than 200 audio tapes and hours of video.

Walker’s archives anchor the exhibit, which exemplifies The Wittliff’s mission of preserving the history of the arts in Texas and the Southwest, inspiring new research, and holding out the possibility of expanding the historical record.

The combination of the music, artifacts, and photography create a “fly-on-the-wall” experience for visitors, similar to the joyous moments in Peter Jackson’s Get Back documentary about the Beatles. The musicians’ youthful energy and enthusiasm is infectious.

★★★

Walker and his ragtag entourage of talented young musicians—who came to be known as the Lost Gonzo Band—didn’t know they were at the forefront of what is now called outlaw country and Americana. But they were the originators.

“All my friends are making this album for me,” Walker is heard saying on one of the newly restored tapes during the first rehearsal of the song “London Homesick Blues.”

“Guy Clark even repaired this guitar,” he added.

Clark’s name wouldn’t have meant much to anyone outside of small music circles at that time. He was among the then-unknown songwriters that Walker adored and spotlighted on the album.

Some of the ¡Viva Terlingua! songs became instant outlaw country anthems—Ray Wylie Hubbard’s “Up Against the Wall Redneck Mother,” Gary P. Nunn’s “London Homesick Blues,” and Walker’s “Gettin’ By” and “Sangria Wine.”

And then there were the storytelling songs of Clark and Michael Martin Murphey, “Desperados Waiting for a Train” and “Backsliders Wine,” and Walker’s haunting tribute to his grandfather, “Wheel.” All were undeniably Texan and deeply personal.

This collection of songs didn’t sound like Nashville country productions. It wasn’t the Bakersfield sound of Buck Owens, nor was it the emerging smoother country rock music of the Eagles and Linda Ronstadt. It was Jerry Jeff music—with a kick.

The Lost Gonzo Band amped up Walker’s folk style, which to that point was his own drifter’s campfire hybrid of Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, Bob Dylan, and Woody Guthrie.

But Walker was also restless and brought a hard-earned experience to the sessions, urgently pushing the young musicians. He hadn’t been satisfied with previous recordings made in New York, Nashville, and even a do-it-yourself effort at Rapp Cleaners in Austin.

There was another factor at play, too.

★★★

Walker had become friends with Hondo Crouch, the larger-than-life, self-styled cowboy poet and storyteller who owned the tiny post office town called Luckenbach, about 10 miles southeast of Fredericksburg. Now a destination dance hall, in the early 1970s Luckenbach was little more than the remnants of a bygone agricultural community fueled by Crouch’s promotional personality.

According to Walker’s widow, Susan Walker, her ramblin’ husband would not have finally settled down in Austin had he not met Crouch. No Hondo, no ¡Viva Terlingua!

Both men were largely invented characters, dreamers. Both had been star athletes in their youth.

It was Walker’s competitive drive and ambition that spurred him to make, whether by accident or not, the ultimate Texas record. “He was fearless,” recalled Newton, the photographer. “Jerry Jeff was the architect. He was the prototype, really.”

Walker cooked up the idea to truck in a mobile recording unit from New York and make a record in the middle of nowhere in a dance hall barn in the August heat. Hay bales served as sound baffles.

The musicians could stay loose—recording, rehearsing, and getting high as they wished. The tape machines would remain rolling throughout. The setting was perfect for Walker, who was known to make up songs on the spot. It culminated with the legendary concert in Luckenbach. The price of admission was $1.

The result was ¡Viva Terlingua!

On the inside of the album’s cover, the music was simply credited to the Lost Gonzo Band: Walker, Gary P. Nunn, Bob Livingston, Herb Steiner, Craig Hillis, Mary Egan, Kelly Dunn, Michael McGeary, Mickey Raphael, and Joanne Vent.

That team effort was key. Walker and the Gonzos were a winning, if short-lived, combination. Their heyday was 1973 to 1976. They’d already gone their separate ways by the time Waylon Jennings scored a huge hit and put Luckenbach on the national map with his 1977 song, “Luckenbach, Texas (Back To The Basics Of Love).”

★★★

A half-century later, ¡Viva Terlingua! feels closer to Bob Dylan’s The Basement Tapes or The Band’s Music From Big Pink. That was Walker’s intent—the laid-back vibe, remote setting, and musical camaraderie.

Contemporaries like Murphey, Doug Sahm, and Willie Nelson were making their country records in New York and Nashville at the time.

A listening station in the exhibit presents audio of an unreleased Houston concert from 1974 that exemplifies Walker and the Lost Gonzo Band’s power. The song “Hill Country Rain,” written by Walker, is a perfect example: Bob Livingston plays piano and sings the opening while saxophonist Tomas Ramirez adds flourishes. Then, Walker takes over and the song becomes as urgent as the rock ’n’ roll of a young Bruce Springsteen. Walker could’ve been the Outlaw Bruce. Nobody on the country scene was doing anything like that.

What made Walker so different, and so willing to take risks, was that he had tasted success—and shown the depth of his songwriting abilities—with his song “Mr. Bojangles.” In the exhibit, visitors can see the earliest known handwritten lyrics of the song, penned by Walker while on a visit to the Guild Guitar Co. in Hoboken, New Jersey, in 1968. A young guitar repairman named John Pascale asked the singer to write them down on the back of some worksheets. Pascale donated them to The Wittliff in 2021.

Walker’s reputation for brawling, boozing, smashing guitars, and all-night partying and drugging in the 1970s made him the original bad boy of outlaw country. That mercurial outrageous side was at odds with the sensitive artist at his core, say his closest friends.

“He was an extremely sensitive person,” said Merri Lu Park, a folk singer and photographer who met Walker in 1965. She recorded Walker singing some of his earliest songs and was a lifelong friend. Park’s photo archive and personal papers are also preserved at The Wittliff.

Lost Gonzo musician Bob Livingston, who played bass, piano, and mandolin in the group, visited the exhibit in September with friend and former bandmate, guitarist Craig Hillis. Livingston couldn’t resist sitting at his old spinet piano on display and sharing stories and singing songs.

A line from Walker’s “Gettin’ By” summed up the attitude behind the whole record, he said: “No matter how you do it. Just do it like you know what you’re doin.’”

“That’s a great line,” Livingston said. “You just do it like you know what you’re doing.”

And that’s how you invent outlaw country. ★

Hector Saldaña is the Texas music curator at The Wittliff Collections.

“¡Viva Terlingua! The Big Bang of Texas Music” runs through Spring 2025 at The Wittliff Collections.

The Wittliff is located on the seventh floor of the Albert B. Alkek Library.

It opens Monday-Friday 8:30 a.m.-4:30 p.m.; Saturdays 11 a.m.-4:30 p.m.; and Sundays 12 p.m.-4:30 p.m.