First-class preparation

by Tracy Hobson Lehmann

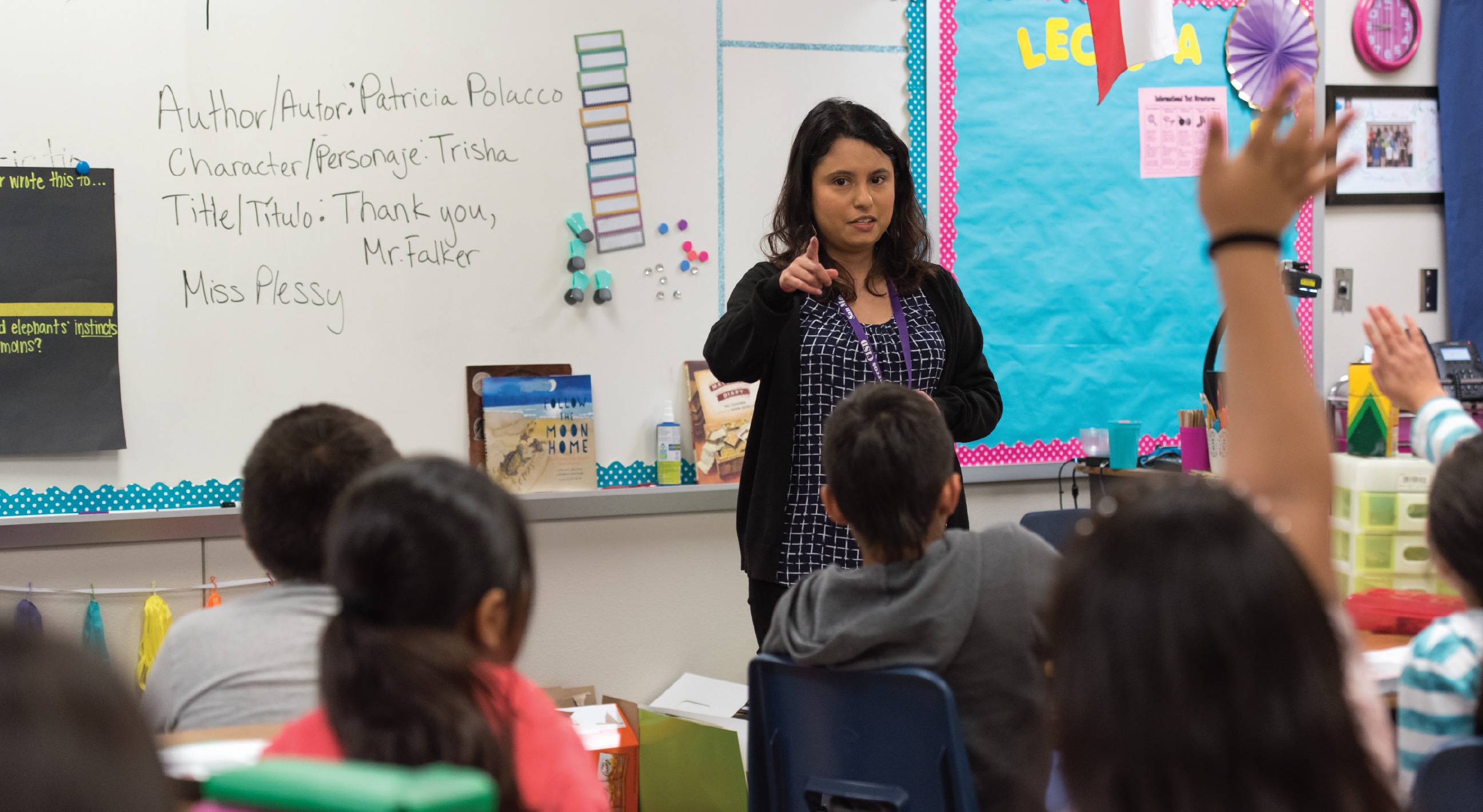

Education majors embedded in area schools get field experience needed for success in the classroom

When Emily Lindsey introduced herself as a student teacher to her seventh-grade writing classes, she did something few adults might: She showed photos of herself as a young teen. She also told students about her experience moving schools when she was their age. Sharing her personal stories, she says, helps connect with students — a lesson Lindsey learned during field block experience.

Field block courses are required in the Texas State University Educator Preparation Program in the two semesters before student teaching. The university is among a handful that pioneered field blocks to enrich the classroom observation hours required by the Texas Education Agency.

"As a classroom teacher, it’s important to get to know students from the get-go," says Lindsey, who wrapped up her bachelor’s degree in education in spring 2018 with student teaching at Dean Leaman Junior High School in Fulshear, southwest of Houston. "They will open up and start to do the work because you’ve sat down with them and acknowledged their struggles."

The program embeds professors and aspiring teachers at schools in and around San Marcos for two days a week throughout a semester. Professors instruct the university’s students and provide feedback as the future educators observe classrooms, lead practice lessons, and get a taste of school culture. The block courses are a hallmark of Texas State’s educator preparation, the largest university-based teacher-certification preparation program in the state. As many as half of the university’s 2,000 education majors participate annually.

"One of the frustrations [teachers] have when they get into the workforce is that it doesn’t look the same as the way they were taught," says Dr. Jodi Patrick Holschuh, professor and chair of the Department of Curriculum and Instruction. "This lets them see a lot of different ways to do things that may not be the way they were taught in class."

The systematic approach helps budding teachers transition from college classrooms — where they learn ideals — to the real world. "A teacher makes about a million decisions every day — more than that, probably," says Dr. Patrice Werner, associate dean for Teacher Education and Academic Affairs. "The only way you can get better is by practicing."

Werner and Dr. Leslie Huling, professor of curriculum and instruction, developed the field block experience concept in 1992 with a $1 million grant from the Texas Education Agency. They collaborated with San Marcos schools to design and implement a program that infuses theory with practice.

"We didn’t want to just teach our classes on campus and then send our students out to the schools," Werner says. "We wanted to have both the teaching and the experience together, and we wanted the professors to be there with the students while the experience was happening. They can help their students process what they are seeing and learning."

After grant funding ended in 1996, the university picked up the reins and now places teachers in more than 20 schools in surrounding districts. The program has expanded to include separate block classes for aspiring elementary, middle, and high school teachers and for those pursuing special education, English as a second language, and bilingual certification. Depending on the student’s plan, field block experience comprises up to 12 semester hours. Coordinators emphasize placements in Title I schools, defined by the TEA as campuses having at least 40 percent of students below the poverty level.

"A teacher makes about a million decisions every day," says Dr. Patrice Werner, associate dean for Teacher Education and Academic Affairs. "The only way you can get better is by practicing."

"A teacher makes about a million decisions every day," says Dr. Patrice Werner, associate dean for Teacher Education and Academic Affairs. "The only way you can get better is by practicing."

At one Lockhart elementary school, coordinators added an extra reading and writing class at the end of the school day so that the Bobcat teachers-in-training were able to offer free after-school tutoring. That’s a win-win.

"It’s helping our students because they’re getting field experience and credit hours, and it’s helping the school give something the students really need," Holschuh says.

Being prepared to teach gives Bobcats an advantage in landing jobs, and it contributes to them staying in the field longer. About 82 percent of Texas State trained teachers remain in the teaching field for at least five years, according to 2017 data, compared to 76 percent statewide.

"Principals and superintendents are always telling us, ‘Please send us more Texas State student teachers because we want to have a crack at hiring them,’ " Werner says.

Isela Rios Guzman, a spring 2017 graduate, reflects fondly on her field block experience. Like Lindsey, Guzman shares personal stories with her fourth-grade bilingual students at Mendez Elementary in San Marcos. She tells them about the demands of field block homework that pushed her to tears and explains that assignments are meant to challenge, not punish them.

When a last-minute switch at her first professional teaching job threw her a curve — teaching fourth-grade bilingual students rather than first-grade dual language students — she took it in stride.

"I was nervous, but I didn’t feel unprepared because I had amazing professors along the way that helped me in my college career," she says. ✪